1K

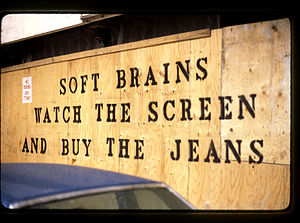

We live in a world where television, billboards, magazines and even toilets are hoarded with sales pitches trying to convince us that a particular brand of soup is what will rid us of our loneliness and make our lives happier. Every day we are bombarded with ideas and concepts to such an extent that we subconsciously start accepting them (almost like Inception). ‘Advertising’ is selling the viewer the idea that consumption (of a particular product) will lead to gratification. In fact, almost all advertisements tap into our insatiable appetite for prestige, power, happiness and status, making the idea quite seductive. Consumerism today has become a pastime, ideology and even a source of addiction. In fact lots of economists and philosophers like to think of consumerism as the singular idea that has successfully taken over the world we live in today. People from all regions, religions and ages indulge in the idea that – more is always better!

But really… is it?

Over the years we have become relatively richer. Businesses have spread, the globe has gotten smaller and we have conditioned ourselves to strive for higher salaries and affluent lifestyles. But has that made us happier? Much like our salaries, rates of divorces, suicides, reports of violence and, not to forget, the number of people suffering of depression, has steadily increased, which makes you really ponder about whether money can really buy happiness.

A recent study conducted by the North-western University, tested how people responded to consumerism and materialism. Results showed that groups that were exposed to images of luxury goods and wordings that rallied consumerist values, showed a higher level of depression and anxiety as compared to those that were shown neutral scenes without consumerist images and words. The former also demonstrated social disengagement and negative environmental behaviour. Economists like to call this, The Modern paradox, where people are progressing materially, but regressing, socially and emotionally.

Can this be one of the reasons why hermits and monks do so well on the happiness scale? Clearly having more choices and going the material way, does not seem to work in the favour of happiness and self-growth. Then why do we pursue it? What makes us so vulnerable to the idea of buying more stuff?

According to a few evolutionary psychologists, the urge to buy more may be deeply embedded in our nature. Studies have shown that young men get a higher testosterone spike when they drive a sports car as compared to driving an ordinary one. This is called the ‘Peacock effect’. Much like the peacock that flaunts its assets to look attractive to its mate and pose competition to its rivals, humans advertise their affluence to look more attractive and desirable. So in effect, in today’s world people like to believe that the possessing affluent goods will make them more desirable.

Although such studies may help us understand our weakness for giving into consumerism, are we also looking for a ‘genetic/ psychological’ reason to excuse ourselves for our consumerist behaviour? It is time we realise the damage we are doing to the environment and ask ourselves isn’t what we have enough. Probably, we should all start following Bhutan’s method of measuring our Gross National Happiness along with our Gross Domestic Product. But for now, like Galen V. Bodenhausen says- watch less TV!

Related articles

- The camouflauge of consumerism (7oakspost.wordpress.com)

- The choices we make (arebelwithacause.org)

1 comment

Thank you for reblogging our post.