778

CTS: Globally, how many labs are involved in this kind of research?

For the current instalment of Researcher of the Month, we spoke to Marie Hornig, a third year PhD student at the Cytology and Evolutionary Biology Department at the University of Greifswald, Germany. Her recently published paper, co-authored by Joachim Haug and Carolin Haug, researchers at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, provides further details about the predator behaviour in mantodeans (animal order that consists of insects such as praying mantis and some 2400 other species). The subject of her study was a praying mantis fossil that is 110 million years old.

A regular day at work for Marie Hornig with co-author Joachim Haug at the Palaeontogical Institute in Moscow.

|

CTS: The smallest of discoveries regarding dinosaurs get highlighted in the media. Here, a fossil preserved over 110 million years exists among us and there is hardly any mention in the media regarding this?

MH: I am fully aware that the focus of media does not represent the recent scientific findings, since non-vertebrate species have never gotten the attention that vertebrates do.

CTS:How do you feel about this?

MH: I sleep well. However, I would be happy if the public would be generally more interested in non-vertebrates such as insects. Scientists, museums and zoos should invest more to advertise these animals especially for non-professionals. Many people are not aware that about 95% of all animal species are representatives of non-vertebrates (about 80% arthropods), so there is much more diversity in invertebrates than what we see in vertebrates. Further investigation of these groups is highly important because it can help us understand more about ecology, evolutionary biology and also aspects in medicine and other areas.

CTS:What can you tell us about this well preserved fossil?

MH:The newly described fossil is preserved in limestone and came from the Crato Formation in the northeast of Brazil, as well as all other known fossils of this species. The Crato Formation was formerly addressed as part of the Santana Formation, were the mantis has its name from. Santanmantis axelrodi was first described by David Grimaldi in 2003. In 2013, we describe a further fossil of this species with a well preserved raptorial leg. The fossil specimen in the current paper is part of the collection of the natural history museum in Berlin, which we visited several times to investigate fossils of different groups of insects.

|

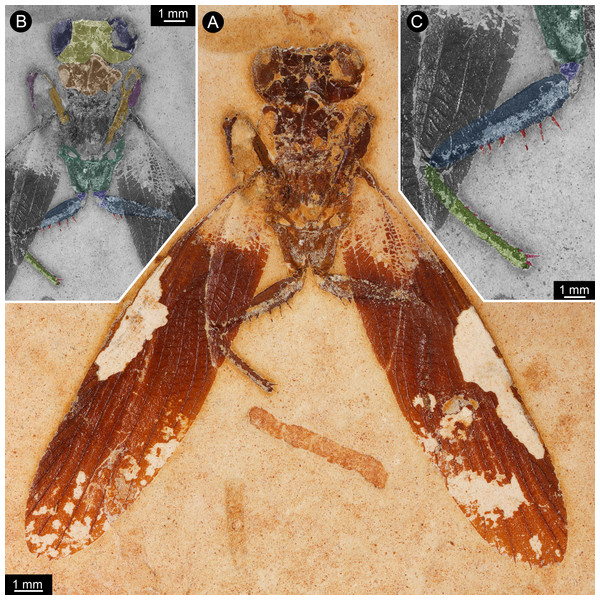

110 million year old fossil studied by the author. Image A shows overview, Image B is the colour marked version of A and C shows details of thorax appendage.Image Credit: 10.7717/peerj.3605/fig-1 |

CTS:Why is it important to study early mantodeans?

MH:Our aim is to gather more information about different groups of non-vertebrates so as to understand about evolution in general. The closest relatives of mantids are the cockroaches and termites, which together are summarised as the group Dictyoptera.

Dictyoptera is a comparably old group. Cockroach-like insects were already common about 300 million years ago and are distributed all around the world today. This group is very interesting for our research, as there is a wide range of lifestyles in this group, ranging from solitary raptorial to social groups.

What we are interested in is the evolution of necessary morphological changes in different kinds of complex behaviour modes. For these organisms, we want to understand when mantids originated in history of our Earth and how the step-wise character evolution from a cockroach-like habitus to the highly specialised morphology of mantids to a raptorial lifestyle occurred.

CTS: Could you please share with our readers the insight that your recent publication has brought to the existing information regarding mantodeans?

MH:This recent publication added some details regarding the morphology of the middle legs on what we have known before about the mantodean species Santanmantis axelrodi.

As fossil remains of praying mantises are comparably rare, every specimen can help to understand more about the morphology and evolution of these insects. Furthermore, we tried to reconstruct some aspects of behaviour based on the known fossils of this species. Maybe the most important message is that early different mantodean species might have had different strategies for prey catching which differs also from the raptorial behaviour of modern Mantodea.

|

Restoration of Santanmantis axelrodi based on the author’s recent work and newly discovered details.

|

CTS: It is easy to imagine predator behaviour in lions, tigers or even dinosaurs. What does predator behaviour in mantodeans look like?

MH: Most modern praying mantises are ambush predators, which capture their prey with their impressive raptorial fore legs.

CTS: Globally, how many labs are involved in this kind of research?

MH: It is difficult to give a number of labs involved. The scientific community is highly dynamic regarding involved researchers and topics.

CTS: Moving a little away, to the process of publication itself. Why did you choose to publish in PeerJ instead of other journals that offer Open Access Publication?

MH:Open access is an important reason for us to choose a journal. Many journals with this option are comparably cost-intensive. PeerJ offers the option of a membership were the authors pay once and can afterwards publish periodically (number of publications per year depends on the kind of membership) without further costs. Furthermore, PeerJ has a broad audience and has no restricting focus to a special field within biological research.

Ms. Hornig will soon submit her thesis towards completion of her PhD.

You can also find more information about research coming out of Joachim & Carolin’s lab on their blog Paleo Evo Devo.