|

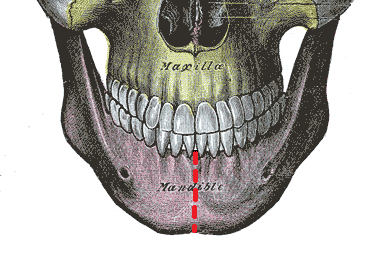

| Image source : Anatomy of the Human Body by Henry Gray (1918) |

The human body has always been a complex structure to study. It never ceases to amaze researchers who recently found a new layer of muscle in the lower jaw. Scientists at the University of Basel, Switzerland discovered an extra muscle layer that sits within the masseter muscle on the back of the cheeks and plays a crucial role in chewing.

What is Masseter Muscle?

The masseter muscle is a strong, thick, paired and rectangular muscle that runs through the posterior part of the cheek to the mandible or lower jaw on each side and closes the jaw during chewing. The masseter is one of the masticatory (chewing) muscles that is accompanied by other muscles such as lateral and medial pterygoid (causes protrusion, depression, elevation of the mandible) muscle and temporal muscle (produce movements in the mandible).

Modern anatomy books described this muscle into two layers. But, now it’s time to update them. The information about this additional layer has been described by the scientists for the first time in the journal Annals of Anatomy.

How Did The Scientists Uncover This New Muscle?

Before this discovery, this muscle was considered to have two parts- one superficial and one deep. Both the parts of the muscle originate from the zygomatic bone (cheekbone) and insert into the superficial (outer) part of the ramus or curved part of the mandible (jaw bone). However, scientists have discovered an additional deep layer after dissecting human heads.

The newly discovered muscle layer runs from the back of the cheekbone to the anterior muscular process of the lower jaw. (S= superficial layer, D= deep layer, C= coronoid layer)

Technically speaking, anatomical texts have described the masseter muscle as one having three layers, the superficial section consisting of two parts while the lower part is called the deep masseter muscle. While most agreed to this description, they were unable to find the actual deep layer. The scientists at the University of Basel, however, dug in deeper to find the mystery of this muscle.

“In the view of these contradictory descriptions, we wanted to examine the structure of the masseter muscle again comprehensively,” said Professor Jens Christoph Tuerp from the University Centre of Dental Medicine, Basel in the statement.

They dissected 12 human cadaver heads preserved in formaldehyde. In addition, they took an MRI scan of the head of the living subject along with CT scans of 16 new cadavers. “This deep section of the masseter muscle is clearly distinguishable from the other two in terms of its course and function,” said Dr Szilvia Mezey from the Department of Biomedicine at the University of Basel.

According to Mezey, this new muscle is involved in stabilising the lower jaw and also helps to move the jaw backward.

Further, the scientists concluded that the discovery is not only significant in terms of understanding the human anatomy but is also useful for clinical purposes. Precise information on masseter muscle will improve therapies and surgery of the lower jaw. It will provide better treatment options to cure lower jaw-related problems.

“Although it’s generally assumed that anatomical research in the last 100 years has left no stone unturned, our finding is a bit like zoologists discovering a new species of vertebrae,” said Tuerp.

Contributed by: Simran Dolwani

To ‘science-up’ your social media feed, follow us on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram!