In the 1930s, anomalous observations of galaxies’ rotation curves unveiled the presence of an invisible type of matter – Dark Matter. In the ensuing decades, a multitude of theoretical models emerged trying to explain what dark matter is made of.

However, theories are not enough on their own. They need to be verified experimentally and observationally. Various teams of scientists across the world are designing experiments to detect the particles predicted by these theories.

These experiments can be divided into three classes – direct, indirect and local production.

Direct Detection

If dark matter is indeed made of particles, then billions of them are probably passing through the Earth every second. A collision between one such particle and the nucleus of an atom could release energy, which could be detected by sensitive equipment. Since such signals could be mimicked by more regular interactions, these detectors are kept deep underground.

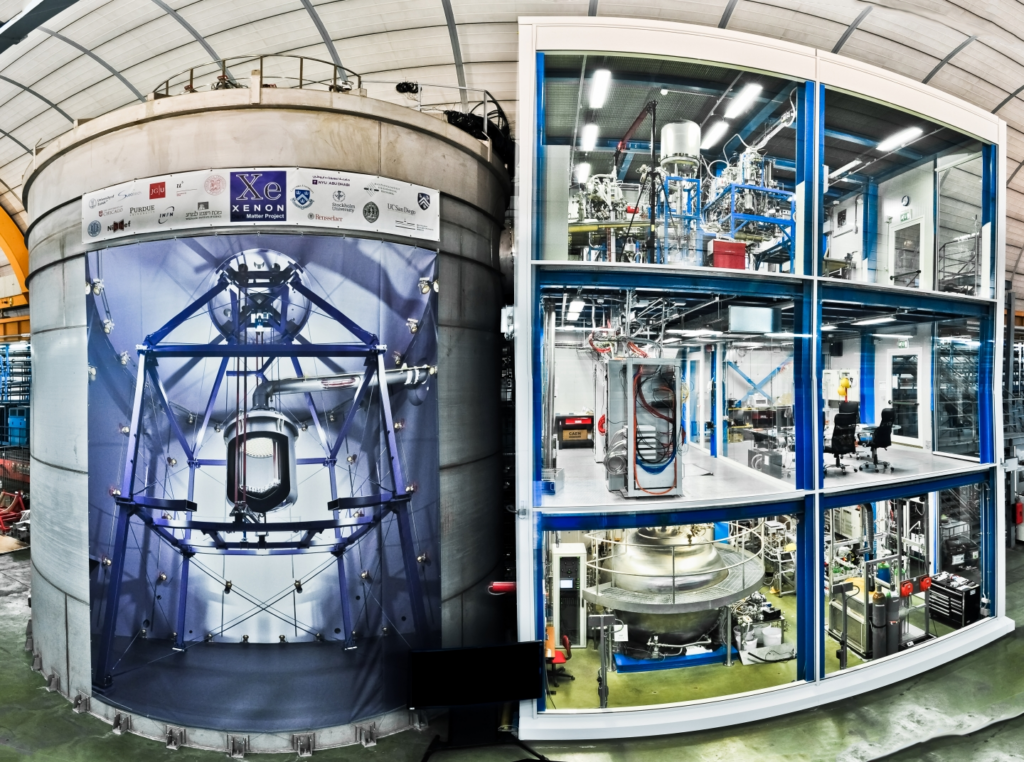

One such experiment is the XENON series of experiments, at the Gran Sasso National Lab, Italy. A tank of liquid xenon is kept almost 1500 meters underground. If a dark matter particle collides with a xenon atom, it will release a photon of energy, which will be detected by sensors placed above and below the liquid.

Even though this system hasn’t detected dark matter particles to date, it is a major player in setting the upper limit on the cross-sectional area of the hypothetical particles. These experiments explore a wide parameter space. A lack of positive result rules out a larger range of dark matter interaction strengths. This helps tighten the constrain on theoretical models and help guide future experiments. The latest iteration of XENON – XENONnT – has significantly refined the upper limit.

The XENON Experiment. Source – https://home.cern/fr/node/4932

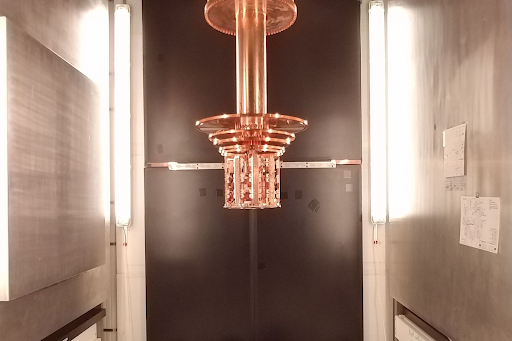

The Gran Sasso National Lab is home to another type of experiment. Instead of using noble gases like Xenon, the Cryogenic Rare Event Search with Superconducting Thermometers (CRESST) employs disks of germanium and silicon that are cooled to around 50 millikelvin and coated in tungsten or aluminum. A dark matter particle (particularly a WIMP) would excite the crystal lattice and send vibrations to the surface, which would be picked up by sensitive detectors.

This experiment, like XENON, has yet to detect dark matter directly.

The CRESST Experiment. Source: https://cresst-experiment.org/

Indirect Detection

The indirect detection method attempts to detect the products of dark matter interactions, instead of dark matter directly. In a region of high dark matter density, two dark matter particles could annihilate to produce normal matter-antimatter pairs or energetic photons such as gamma rays. Alternatively, a dark matter particle could be unstable and decay into normal matter particles.

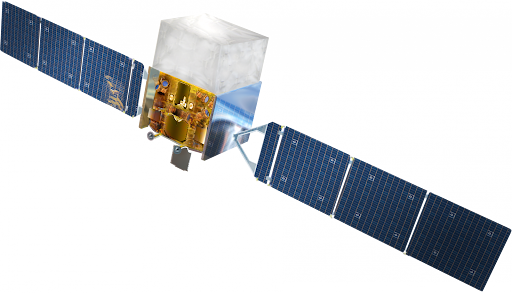

Telescopes such the VERITAS, MAGIC, Fermi and H.E.S.S. have been searching the sky at gamma-ray wavelengths. Any increase in the normal gamma-ray photon distribution in the universe could be attributed to collisions between dark matter particles.

The Fermi Gamma Ray Telescope. Source – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fermi_Gamma-ray_Space_Telescope

Gamma Ray searches are complemented by cosmic ray searches. The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), aboard the International Space Station (ISS) is a particle detector that analyzes cosmic rays. It looks for excess in background positrons, antiprotons, or gamma-ray flux, which could signal the presence of dark matter particles.

The AMS Module. Source – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alpha_Magnetic_Spectrometer#Specifications

However, similar to the direct detection case, other than placing limits on various theoretical parameters, no positive result has come forth.

Local Production

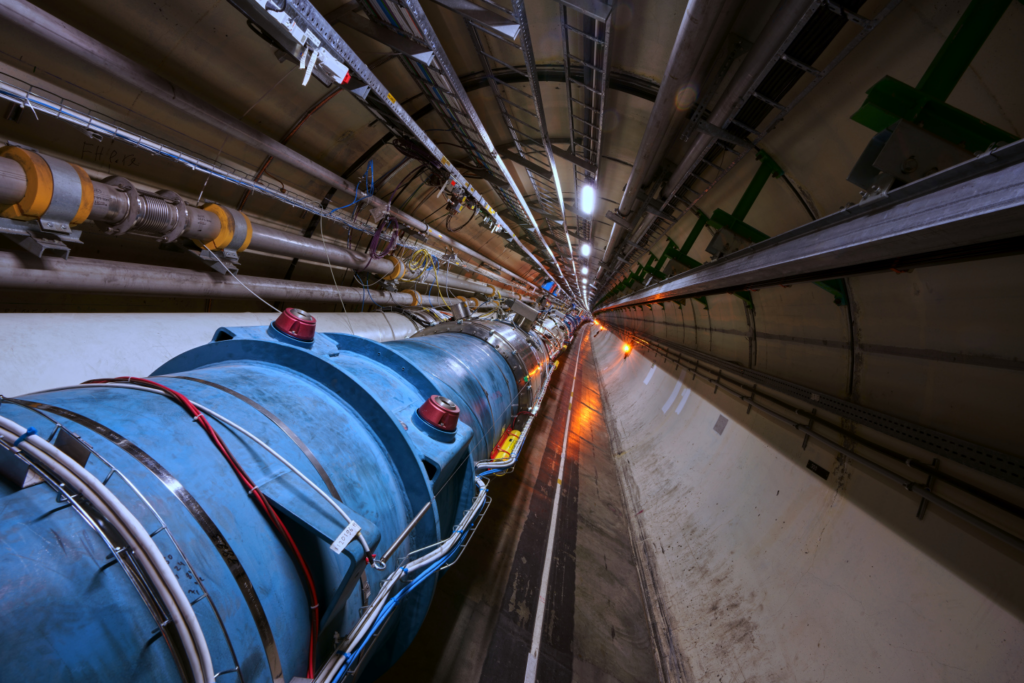

The third class of experiments is trying to produce them in laboratories on Earth itself. When two subatomic particles, such as protons, collide with each other while moving at speeds comparable to that of light, dark matter particles could be produced. Their presence could be detected by observing any unusual loss in energy or momentum throughout the collision process. Particle colliders such as the Large Hadron Colliders (LHC) are the hotspots for such experiments.

The Large Hadron Collider. Source – https://home.cern/science/accelerators/large-hadron-collider

Where does this leave us?

Dark matter has become a century-long problem in physics. Even though we are sure about its presence and its pivotal role in shaping our universe, we are nowhere close to understanding what makes it tick. In the last three decades, nearly 60 thousand refereed papers have been published about this invisible matter, and yet we are barely scratching its surface.

However, all hope is not lost. With each increment in our technology’s prowess, we crack open the mysteries of the universe a step further. Improved simulations and theoretical models will help us constrain our observational attempts better, which will, in turn, increase the chances of detecting this elusive matter.

It’s just a matter of time.