797

For those who might not be aware, the city of Karachi in Pakistan has been afflicted with the deadly disease of dengue for many decades. At the time of writing this post, there are 2896 dengue fever cases reported in the province of Sindh in Pakistan this year, of which 2829 are reported in Karachi alone. It is only a matter of time, before the virus manages to spread elsewhere and becomes a full blown epidemic in the country, The effective method to counter this would be to take precautionary measures during monsoon but predictions on how the virus might spread can also help in concentrating efforts in high risk areas to avoid major outbursts. To do this, the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health collaborated with Telenor, a Norwegian telecom company offering telephony services in Pakistan and monitored call records of about 40 million telephone subscribers between the period of June 1 to December 31 of 2013.

For those who might not be aware, the city of Karachi in Pakistan has been afflicted with the deadly disease of dengue for many decades. At the time of writing this post, there are 2896 dengue fever cases reported in the province of Sindh in Pakistan this year, of which 2829 are reported in Karachi alone. It is only a matter of time, before the virus manages to spread elsewhere and becomes a full blown epidemic in the country, The effective method to counter this would be to take precautionary measures during monsoon but predictions on how the virus might spread can also help in concentrating efforts in high risk areas to avoid major outbursts. To do this, the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health collaborated with Telenor, a Norwegian telecom company offering telephony services in Pakistan and monitored call records of about 40 million telephone subscribers between the period of June 1 to December 31 of 2013.

|

| Edward Snowden |

The face of Edward Snowden is etched in history as the man who brought out in the open the mass surveillance programs run by the National Security Agency of the United States. While the very idea of mass surveillance raises questions about the government’s right to mine data, keep its programs classified for purposes of national security and also our right of privacy in this digital age, there is also the other side of the coin, which we are failing to look at, the side where mass surveillance can be used in a positive manner, to help people. This is the kind of surveillance, Telenor did in Pakistan.

Surveillance of phones in Pakistan

For those who might not be aware, the city of Karachi in Pakistan has been afflicted with the deadly disease of dengue for many decades. At the time of writing this post, there are 2896 dengue fever cases reported in the province of Sindh in Pakistan this year, of which 2829 are reported in Karachi alone. It is only a matter of time, before the virus manages to spread elsewhere and becomes a full blown epidemic in the country, The effective method to counter this would be to take precautionary measures during monsoon but predictions on how the virus might spread can also help in concentrating efforts in high risk areas to avoid major outbursts. To do this, the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health collaborated with Telenor, a Norwegian telecom company offering telephony services in Pakistan and monitored call records of about 40 million telephone subscribers between the period of June 1 to December 31 of 2013.

For those who might not be aware, the city of Karachi in Pakistan has been afflicted with the deadly disease of dengue for many decades. At the time of writing this post, there are 2896 dengue fever cases reported in the province of Sindh in Pakistan this year, of which 2829 are reported in Karachi alone. It is only a matter of time, before the virus manages to spread elsewhere and becomes a full blown epidemic in the country, The effective method to counter this would be to take precautionary measures during monsoon but predictions on how the virus might spread can also help in concentrating efforts in high risk areas to avoid major outbursts. To do this, the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health collaborated with Telenor, a Norwegian telecom company offering telephony services in Pakistan and monitored call records of about 40 million telephone subscribers between the period of June 1 to December 31 of 2013.

To clarify, call records, mean anonymised and aggregated data of telephone subscribers that would give enough data to know where users were usually located (home) and where they travelled to, incase they moved away from the home locations and not actually phone transcripts. (For data privacy buffs reading this, no data actually left the country during the entire research process). Based on the data, the researchers were able to create a map of travel that mobile phone users took during the period of the study.

Other data such as model for spread of virus, temperature conditions suitable for spread of the disease and estimation of travel undertaken by affected individuals was overlaid on this data to arrive at estimates of how the disease could spread. Ground data was then analysed to see how the prediction actually fared and has been summarized in the image below.

The model used by the researchers was able to get the timing of the fresh case right ( within reasonable error limits) in the city of Lahore and even remote areas of Mingora correctly,. Additionally, the mobile phone data also allowed researchers to correctly predict locations that carried higher risks of epidemic outbreaks, an important piece of information for healthcare professionals when combating diseases such as dengue.

Surveillance of WikiPedia in 9 countries

It is amazing what we are comfortable telling our computers but not our near and dear ones. Your family physician might not be aware of the mole you are developing on your skin, but your computer has clarified has some doubts for you, when the fact is that you are better off talking to your physician about it rather than interpreting suggestions from WebMD.

Researchers Nicholas Generous and his colleagues at the Los Alamos National Laboratory questioned whether this frankness to our computing devices, to our search engines, could actually be used positively. Harvesting three years of search queries on Wikipedia, in nine different countries, the researchers wanted to know if search queries could be used to predict the onset of a disease in a particular location. Using a combination of 14 disease to location combinations, the researchers surveyed health related queries in 8 languages to create a model of how the disease was progressing and later matched it to the official records of progression as monitored by local health agencies.

This comparison worked successfully in 8 out of the 14 tested scenarios.

| The above image shows how model of disease progression from Wikipedia based data coincides with local health records. Image credit: Nicholas Generous et al DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003892 |

Amongst the scenarios, where this model could not be applied is the spread of HIV/AIDS. Although, the disease is lethal, its spread is much slower when compared to dengue, other diseases and the model could not be applied for prediction.

Another reason for failure of models in certain areas would be lack of internet connectivity available to all users. Therefore, the model derived for the disease-location combination is skewed towards a certain set of population and does not agree with data gathered at the ground level.

Surveillance of Social Media

|

| Image credit: www.betterplaced.com |

Social media such as Twitter, Facebook and others are often outlets for users to inform their family and friends about their well being. While a tweet about being sick from an individual may seem pointless, tweets from hundreds of users around a similar time period can be quite useful for purposes of disease surveillance. In Chicago, the Department of Public Health analyzes tweets from the city to determine incidents of food poisoning in the city and accordingly carries out inspections to zero in on non hygienic places to eat.

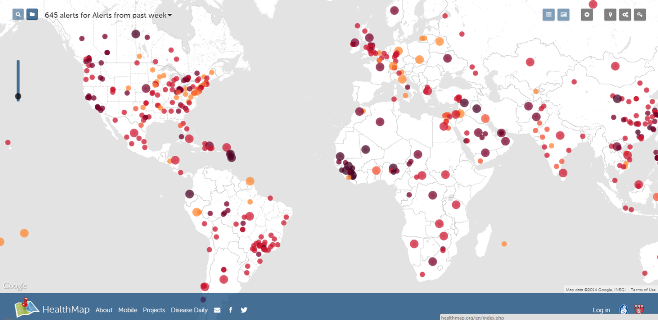

Taking it a step further HealthMap analyzes content from social media, blogs,chat rooms and even mainstream media and monitors trends of emerging diseases and makes it freely available for all.

With continuing research and developing technology, disease surveillance will only get better from here on. All we need to do is support such ‘mass surveillance’ and encourage our governments to do the same.

If you would like to read more of these interesting stories from the world of science, subscribe to our blog and we will send you an email every time we post something new and interesting. Alternatively, you can follow us on social media such as Facebook, Twitter or Google Plus!

References:

References:

Wesolowski A, Qureshi T, Boni MF, Sundsøy PR, Johansson MA, Rasheed SB, Engø-Monsen K, & Buckee CO (2015). Impact of human mobility on the emergence of dengue epidemics in Pakistan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112 (38), 11887-92 PMID: 26351662

Generous, N., Fairchild, G., Deshpande, A., Del Valle, S., & Priedhorsky, R. (2014). Global Disease Monitoring and Forecasting with Wikipedia PLoS Computational Biology, 10 (11) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003892

Schmidt CW (2012). Trending now: using social media to predict and track disease outbreaks. Environmental health perspectives, 120 (1) PMID: 22214548