Diego Ellis-Soto, MS

Humans have benefited from animals for millennia: from canaries in coal mines to man’s best friend, we often depend on animals to keep us safe, fed, and entertained, and in turn, we try to protect animal species as best we can. But global warming is threatening all of our habitats, so this symbiosis must go deeper. As the climate continues to rapidly change, we need more weather data than ever to form accurate predictions. Animals equipped with sensors can collect weather data as they go about life, and we can in turn learn more about how to protect them – and ourselves – from a dramatically changing climate.

To learn more about the future of animal-borne sensors, we interviewed Diego Ellis-Soto (DES), a Ph.D. candidate in Yale University’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the Yale Center for Biodiversity and Global Change. ecolo

CTS: What sort of information do we currently get from animal-borne sensors, and why are animals better at obtaining this information than humans or robots?

DES: One difference about animals collecting data is that they can go where we and our robots can’t. During winters in antarctica, for example, elephant seals can dive down in the water and collect temperature and salinity data. There are probably fewer than 10 icebreaking ships in the world that can collect these data profiles. Animals can exist in places like antarctica, the pacific islands, and cloud and rain forests – regions where there are very few weather stations, and so they can fill in important gaps that complement our weather forecasting systems.

We most commonly put transmitters on sea animals that measure sea surface temperature, air temperature and salinity. In fact, 80% of our ocean measurements in Antarctica are collected by elephant seals – without them, we would have no idea that the arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world due to climate change! I’ve also seen cases where people measure chlorophyll levels, which tells you how much plant productivity there is in the ocean, which is really important for understanding the marine ecosystem but difficult to measure due to water currents.

Animals can also help us better understand extreme heat advisories and pollution in cities. Several years ago in London and Mongolia, [researchers] put tiny sensor backpacks on pigeons in a city to measure local urban heat and air pollution. Measuring air pollution is typically very hard and often needs drones, which require permitting, bother people and animals, and are very expensive. But with a homing pigeon, you can literally throw them out [into the world] and they’ll come back at the end of the day. Those programs in London and Mongolia were trials and have since stopped, but how cool would it be if we had pigeons flying from one place to another every day measuring air pollution?

Image source: Pixabay

CTS: How do you think we can expand animal-borne sensors to learn more about climate change?

DES: With climate change, we want to have more accurate, high-resolution predictions of what’s happening locally during increasingly extreme events, like heat waves and floods. It’s very hard to plan an experiment for these events because they are hard to predict and don’t last a long time, but animals that are continually collecting data can tell you what the area was like before, during, and after the extreme event.

This influences how we think about how threatened species will behave under climate change. It turns out that animals don’t really care about gradual changes in temperature – they care about the fast and extreme changes, like going from 80°F normally to 120°F. With animal-borne sensing, we can observe whether an animal is going to be completely screwed [by climate change] or not. For example, some animals can literally just fly away from a heat wave, some mammals might burrow, but some animals can’t move away.

Animal borne sensors are tools that can be used to assess some key aspects of climate change: the increase of severity in extreme events, and how an animal might cope in a world where these are more normal. This is important for their conservation, and also for our understanding of how climate change might affect us.

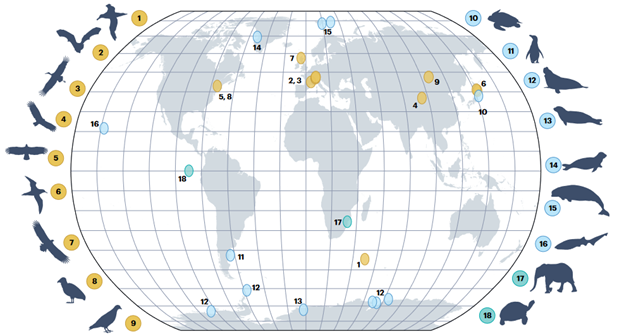

Locations on earth where animal-borne sensors are currently deployed, according to animal type. Image Source: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01781-7

CTS: Your article also discusses this in the context of identifying microrefugia. What are microrefugia, and how might we protect them?

DES: Microrefugia are places where it’s still a great habitat for the survival of species even during adverse conditions. A really common example is during the ice age when the glaciers formed, there were these tiny valleys where a bunch of plants survived when they went extinct everywhere else. Then when the glaciers melted, the plants started to expand again from those valleys. The valleys can therefore be considered a microrefugia for those plants. We can think about it similarly for, say, a migratory bird that stops a lot during its journey, like a crane. Cranes migrate over a large expanse but take a lot of stops to eat and rest. The places where they stop can be microrefugia, like a patch of forest near a river amid a very dry and hot desert – that’s a microrefugia. That’s a critical habitat that can supply refuge under adverse conditions.

When we plan for national parks, we think about these very vast natural areas, which are really hard to protect since they require a lot of political momentum and money. But if we can identify the tiny forest by a stream or a pond that’s a microrefugia, we can more surgically protect these habitats in a way that’s cheaper and more realistically feasible. In conservation biology, this principle is called “single large or several small” which asks the question: do we need one big national park, or a hundred tiny ones? A lot of people, especially in cities, are saying we’ll never be able to make a big national park again because there are too many people, but we can make a hundred small [national parks], and these should include the microrefugia.

CTS: Based on your research, how do you predict the animal kingdom will change as a result of climate change?

DES: It’s context-dependent, which is why we need this context-dependent weather information collected by animal-borne sensors. We know that species’ populations are across the earth such that a lot of species are moving towards the north and south poles. Animals are also moving up mountains because its getting warmer, and that’s pretty dangerous because there’s only so high you can get up on a mountain. One thing that’s important to note is that these redistributions are going to affect entire communities and ecosystems because new species will arise and could change the ecology in that area.

CTS: How do you hope your publication will influence the field of ecology?

DES: I think for climate change and for terrestrial animals, I would love to see the integration of temperature and humidity. “Hot and dry” is really different from “hot and [humid]”, and this is why we define the “wet bulb temperature”, which takes humidity into account, when looking at heat strokes in humans. [This data] would also be good for meteorologists, so I’m working a lot with NASA to propose interdisciplinary teams that work towards a grand deliverable using joint funding, because meteorologists usually have big budgets and ecologists are typically underfunded, but we can all benefit from this type of data.

The details of the research have been published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

If you enjoyed reading this post, please subscribe to our newsletter or Visit our Shop to buy some geeky science merchandise.

2 comments

[…] It is also mandatory for operators to employ at least one independent protected species observer on duty at all times during the day and at least two at night to detect protected species and avoid any contact. Ultimately, all policies are carried out with an emphasis on mitigating the impact of wind farm construction on marine life and reversing the drastic effects of climate change. […]

You’ve addressed some very important points, kudos for bringing them to light.