Stillbirth is one of the most heartbreaking situations that a couple can experience. It is tragic and frustrating, especially when you don’t know why it happens. Certain health issues in pregnant women can be a reason, but a new study by researchers at the University of Utah Health, U.S., suggests that stillbirth can be inherited and passed down through male family members. This means the risk comes from the father’s and mother’s patriarchs, including their fathers, grandfathers, brothers, uncles or male cousins. The chances for stillbirth for a couple increases when the condition comes from the paternal side.

What causes stillbirth, and how common is it?

According to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in every 175 births in the U.S. is a stillborn case. The exact reason for stillbirth is unknown. However, doctors say that the risk increases when the mother suffers from severe health conditions such as diabetes, gastrointestinal hypertension or pre-eclampsia, a serious pregnancy complication characterised by high blood pressure.

Stillbirth and genetics

To determine the causes and risk factors for stillbirth, the researchers analysed 18,808 live birth and 9,404 stillbirth cases between 1978 and 2019. The data was collected from Utah Population Database (UPDB), a data resource having birth, death and health records used for research purposes.

The researchers discovered that 390 families had the highest number of stillbirths over multiple generations. This indicated that stillbirths are linked to genetics. They compared the incidences of stillbirth in babies from their first, second and third-degree relatives affected by it with unaffected relatives or families. Their evaluation revealed that an increased risk of stillbirth was passed down through male members, an unusual but fascinating point that wasn’t highlighted before.

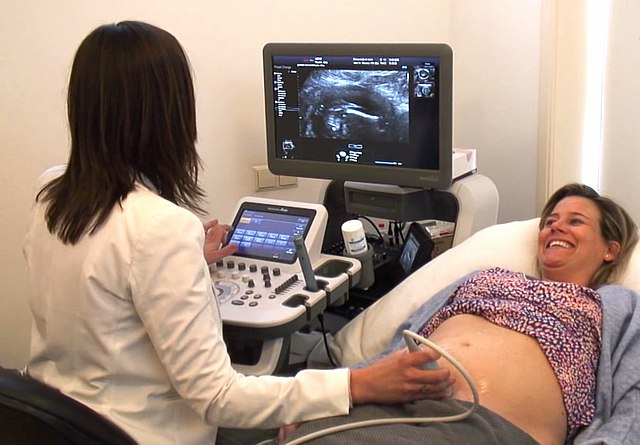

Image Credits: Pixabay

“We were able to evaluate multigenerational trends in fetal death as well as maternal and paternal lineages to increase our ability to detect a familial aggregation of stillbirth,” said Tsegaselassie Workalemahu, the study’s author. “Not many studies have examined inherited genetic risk for stillbirth because of a lack of data. The Utah Population Database (UPDB) allows for a more rigorous evaluation than has been possible in the past.”

Future expectations

According to Workalemahu, studying pregnancy can help improve the health of future generations. Identifying patterns and common links of stillbirth in families can help doctors calculate the risks or probabilities. Further, the study could help to discover specific genes linked with stillbirth and provide scope for better diagnosis and prevention.

“Stillbirth rate reduction has been slow in the U.S., and we think many stillbirths may be potentially preventable,” said Jessica Page, the study co-author. “This is motivating us to look for those genetic factors so we can achieve more dramatic rate reduction.”

The research was published in the journal BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology.

To ‘science-up’ your social media feed, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram!

Follow us on Medium!