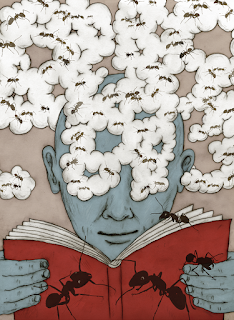

Like a brain, an ant colony operates without central control. Each is a set of interacting individuals, either neurons or ants, using simple chemical interactions that in the aggregate generate their behaviour. People use their brains to remember. Can ant colonies do that? This question leads to another question: what is memory? For people, memory is the capacity to recall something that happened in the past. We also ask computers to reproduce past actions – the blending of the idea of the computer as brain and brain as computer has led us to take ‘memory’ to mean something like the information stored on a hard drive. We know that our memory relies on changes in how much a set of linked neurons stimulate each other; that it is reinforced somehow during sleep; and that recent and long-term memory involve different circuits of connected neurons. But there is much we still don’t know about how those neural events come together, whether there are stored representations that we use to talk about something that happened in the past, or how we can keep performing a previously learned task such as reading or riding a bicycle.

A red wood ant colony remembers its trail system leading to the same trees, year after year, although no single ant does. In the forests of Europe, they forage in high trees to feed on the excretions of aphids that in turn feed on the tree. Their nests are enormous mounds of pine needles situated in the same place for decades, occupied by many generations of colonies. Each ant tends to take the same trail day after day to the same tree. During the long winter, the ants huddle together under the snow. The Finnish myrmecologist Rainer Rosengren showed that when the ants emerge in the spring, an older ant goes out with a young one along the older ant’s habitual trail. The older ant dies and the younger ant adopts that trail as its own, thus leading the colony to remember, or reproduce, the previous year’s trails.